The following article authored by Dylan Baddour was originally published in the Houston Chronicle. Reprinted with permission. Jaime Ramos worked picking ornamental ferns in Florida until he got ready to start a family. He took a higher-paying construction job, but then found himself frustrated by a transient labor force that learns as it goes.

Jaime Ramos worked picking ornamental ferns in Florida until he got ready to start a family. He took a higher-paying construction job, but then found himself frustrated by a transient labor force that learns as it goes.

“There are people who’ve been doing this for years and sometimes they don’t know they’re doing something the wrong way,” he said recently. “Just nobody ever taught them.”

Workers came and went. No one got benefits. There was barely opportunity for advancement. Ramos knew it was no place to build a future.

Then he got a call from a brother-in-law in Houston, who told him about one contractor, Marek, that offered a training program and a real career path. So Ramos moved here and took advantage of Marek’s classes. Six years later, he’s a company foreman with a promising future in management.

Without training from Marek, Ramos said, “I’d be job-hopping like the other friends I have.”

Ramos is both an exception in the modern construction industry and exactly the kind of worker that local employers are struggling to cultivate amid a generations-long downturn in the skill and availability of construction labor.

“I’ve yet to run across anybody who doesn’t agree that the industry has a workforce problem,” said Chuck Gremillion, executive director of the Houston-based Construction Career Collaborative (C3), which since 2009 has worked with contractors and project owners to improve their employment standards.

While local community colleges Houston, San Jacinto and Lone Star help prepare students entering the trades, C3 tries to rally contractors to work with the existing labor pool and make the industry more attractive.

That’s a tall task. C3 faces a complicated problem at the intersection of low wages, dangerous work, poor benefits, the scaling back of vocational courses in public schools, and loss of craft training programs once offered by labor unions. Quickly fading are the days of career painters, bricklayers, and drywall hangers.

C3 has taken aim at all of these factors, teaching safety protocol, enforcing good employment practices among its accredited contractors and focusing on craft training as part of a long-term solution.

“We’ve seen this decrease in the availability and the skill level of the workforce over many years,” said Katrina Kersch, chief operations officer for the National Center for Construction Education and Research in Washington, D.C. “The lack of training is why we believe we’re in a workforce shortage.”

The problem is most acute in quickly growing regions with high labor demand, like Texas. Large segments of the construction workforce operate as independent subcontractors drifting from sector to sector without the benefits of full employment, usually learning the craft with no formal training.

Lack of training also harms the bottom line. Research from 2014 from the Construction Industry Institute at the University of Texas found that if 1 percent of project costs were invested in workforce training, productivity rises 11 percent, injuries fall by 26 percent and the amount of work that must be redone falls by 23 percent.

“If there’s a limiting factor in Houston growing, it would be a skilled workforce,” said Jim Stevenson, Houston division president for McCarthy, a contractor accredited by C3.

C3, which hired its first three paid staffers in 2014, now is working to bring on a “craft training champion” by month’s end to encourage and foster in-house training programs at contractors across the city. As Gremillion tells it, the training problem began with the decline in union membership beginning in the 1980s. The unions, he said, traditionally offered craft training.

Nelson Lichtenstein, director of the Center for the Study of Work, Labor and Democracy at the University of California, Santa Barbara, said major employers’ longstanding focus on lowering wages also contributed to the current situation.

C3 shares office space with the local branch of the Associated General Contractors of America, which Lichtenstein said generations ago encouraged the use of non-union labor. The industry, he said, is “complaining about something they helped create.”

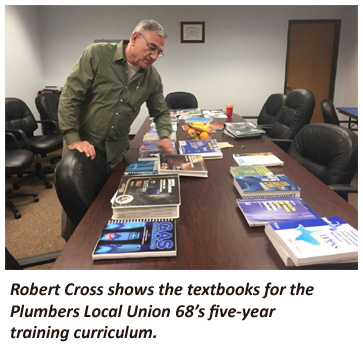

But unions aren’t totally dead. Particularly for trades like electricians, HVAC techs, or plumbers that require state licenses; union training programs remain robust. At the Plumbers Local Union 68 in north central Houston, director of training Robert Cross spreads about three dozen textbooks across a conference room table – the material for the five-year program to become a certified journeyman plumber. Books range from basic safety to math to “Drawing Interpretation and Plan Reading.”

At the Plumbers Local Union 68 in north central Houston, director of training Robert Cross spreads about three dozen textbooks across a conference room table – the material for the five-year program to become a certified journeyman plumber. Books range from basic safety to math to “Drawing Interpretation and Plan Reading.”

The union has 35 part-time instructors, 16 classrooms and computer labs with projector screens, and six shop areas stocked with pipe cutting and welding stations or mock-ups of hospital gas systems, refrigeration coils, an office tower mechanical closet, and a bathroom plumbing system.

Local 68 has roughly 1,900 members, plus about 600 students who spend 246 classroom hours and 600 hours apprenticing for certified plumbers each year for five years. The program is funded through deductions from members’ wages, which are $44.34 per hour under union negotiation.

“These programs take a lot of energy, a lot of effort,” Cross said. “This is the type of school that C3 would like to see their contractors bring back for all their crafts.”

C3 has about 230 accredited contractors in Houston.

The companies have agreed to hire workers as hourly employees, not subcontractors; to pay overtime and offer compensation insurance; to provide federal safety certification; and to express an intention of building an in-house craft training program.

After hiring a training manager, C3 will assess each company’s progress in developing their own programs.

Some have already launched. Ramos, for example, started at Marek as a helper hanging drywall, while also taking courses on materials and processes, codes and regulations, reading blueprints, and the economics of budgeting. He eventually earned a certification to coach other students.

Marek started the training program about 10 years ago.

“The industry wasn’t doing as well attracting people because they didn’t see paths for growth,” said Sabra Phillips, Marek’s director of talent development. “We felt like we needed to do our part to contribute to solving this.”

McCarthy is also opening a new office building east of Houston with a dedicated craft training facility for employees.

To encourage more such programs, C3 is developing a blueprint for other companies seeking to build such training programs.

Major projects that have opted to use C3-accredited contractors include an expansion of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston currently underway; a new pediatric tower for Texas Children’s Hospital; and expansions for Memorial Hermann in the Texas Medical Center and for an MD Anderson Cancer Center in League City.

Peter Dawson, senior vice president of facility services at Texas Children’s and a member of the C3 board, said accreditation like this reduces instances of “substandard construction quality.”

“This is of long-term benefit to those who own and operate the facilities,” he said.

Photos courtesy of the Houston Chronicle